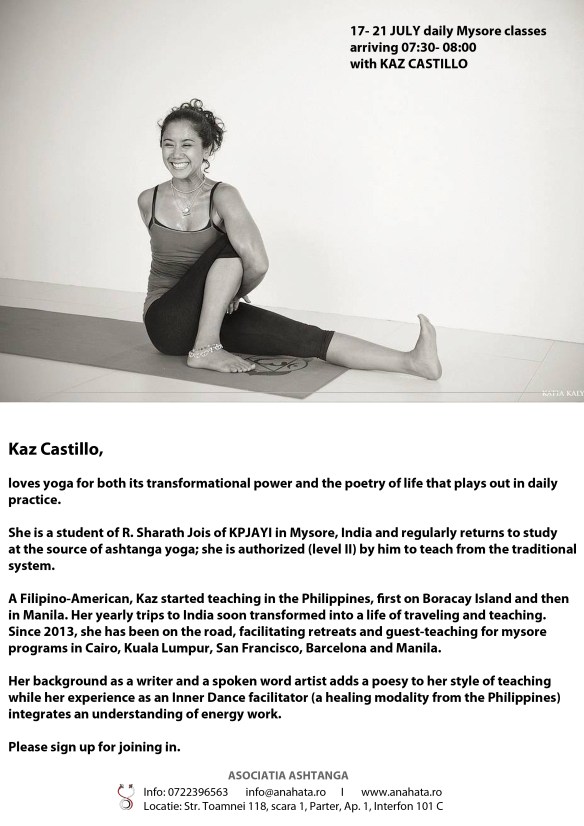

Photo by Michael Tutaan, Boracay, Philippines

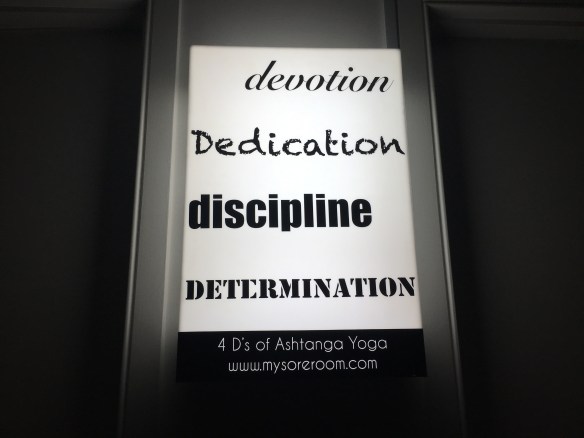

The great irony, perhaps, of diving deeper into this physical practice is how metaphysical it becomes, the more advanced the posture, the more subtle the mind and the heart. How, for example, taking one’s leg behind the head is less about the openness of hips, the ability to internally rotate the leg while lifting the center and, with it, the back–though all fundamentally a part of the process–than it is about cultivating patience and perseverance.

Once in a while, I ask myself, what have I learned? What is new, especially when there are no new postures to investigate or obsess about? It has been two years, almost, since I’ve studied with my teacher in Mysore and my practice seems to be greatly about establishing a steady rhythm, building strength and getting comfortable. Some days are tougher than others, I must admit, developing strength seems to have come with loosing a certain amount of bendiness. And establishing a life in one place, as I have done this year in Egypt, comes with an entirely different set of challenges that sometimes get in the way of the smooth flow of practice.

For me, I think one of the greatest lessons of cozying up to the intermediate series these last two years is learning to forgive myself. I may have not overcome my own expectations, they creep up on me still while on the mat (not to mention off the mat!), but it’s never so hard as before. Mostly, because I’m not as hard on myself as I was before. Often, I find myself humorously observing the struggles, the days I ate pasta and how that feels in titthibhāsana, the days I can’t get a good grip on the mat in karandavāsana and fall, the days I get on the mat late and I’m so tired that I’m practically crawling through the practice. It’s all ok, I can’t always be my best physically though I can still put my best effort forward based on the conditions that I am given and that I allow myself.

We cause so much undue suffering with unforgiving thoughts: why can’t I do it, what’s wrong with me, why am I not good enough? Such fluctuations of the mind are debilitating, they stall us, not just mentally but physically too, they keep us from moving forward. And thus the relationship between the mind and the body continues. So, instead, let’s be kind to ourselves, let’s be sweet and also honest. Be honorable, admit when it’s hard but do not harden because of it. Forgiveness in itself is a deep and fulfilling practice.